Starship IFT-11 is another success but it maybe too late for SpaceX to hold off HLS competitors

After having a very successful IFT-10 test flight for its Starship-Super Heavy combination, SpaceX repeated the feat with its last ever flight of the v2 version of ahead of its planned move to a fully orbital v3 version. This latest test flight dubbed IFT-11 lifted off from its Starbase launch site, near Boca Chica in Texas, USA at 2323 GMT on 13 October 2025. All 33 Raptor engines fired successfully during the first stage burn. This was followed by a hot-staging two minutes 39 seconds into the flight in which Starship's six engines are fired just before first stage separation. As planned, the Super Heavy Booster 15 on its second flight, did its flip over manoeuvre and burn to fire itself back to the Gulf of Mexico (Gulf of America) where it used 12 engines (of 13 planned to be fired) to slow itself into a soft splashdown after a brief hover - a new technique being tested for future missions.[caption id="attachment_123738" align="alignnone" width="834"]

On board TV view of imminent splashdown of Starship Ship 38 on its IFT-11 test flight. Courtesy: SpaceX[/caption]Meanwhile, Starship Ship 38 on its first flight, carried on its suborbital trajectory at near orbital velocity. Just after engine shut off Starship deployed eight dummy satellites (simulated Starlink communications satellites) and then made a a relighting of one of its vacuum optimised Raptor engines in a simulation of a de-orbit burn.

Starship re-entered the Earth’s atmosphere and was able to gather extensive data on the performance of its heatshield as it was intentionally stressed to test the limits of the vehicle’s capabilities. In the final minutes of flight, Starship performed a 'dynamic banking manoeuvre' to mimic a turning manoeuvre that future orbital missions returning to Starbase will fly. One hour and six minutes after lift off, at 0029 GMT on 14 October, Starship then guided itself using its four flaps to the pre-planned splashdown zone in the Indian Ocean, successfully executing a landing flip, landing burn, and soft splashdown. The upper stage still showed orange coloured oxidation of its other thermal protection system, an indication that rapid reuse without extensive renovation may still be out of reach for SpaceX.

The descent and landing of the Starship craft can be seen here:https://x.com/SpaceX/status/1978179844656480423

Starship schedule delays might mean that SpaceX misses out on lunar landing glory

Despite this launch success, SpaceX is running well behind its schedule to test its Starship HLS (Human Landing System) ahead of its planned Artemis 3 landing mission. Thus, realising this, and mindful that China is close to making its own human landing attempt, NASA's acting administrator Sean Duffy has asked for the HLS (Human Landing System) lunar landing craft competition to be restarted.

“We’re opening this up to Blue Origin and maybe others to foster competition and get us back to the Moon before the end of President Trump’s term in January 2029.” said Duffy.

This will cause Blue Origin to either accelerate the building of its Blue Moon Mk2 human lunar lander and ascent vehicle - a derivative of its Blue Moon unmanned lunar lander or possibly build a smaller lander based on its already flying unmanned Mk1 version.

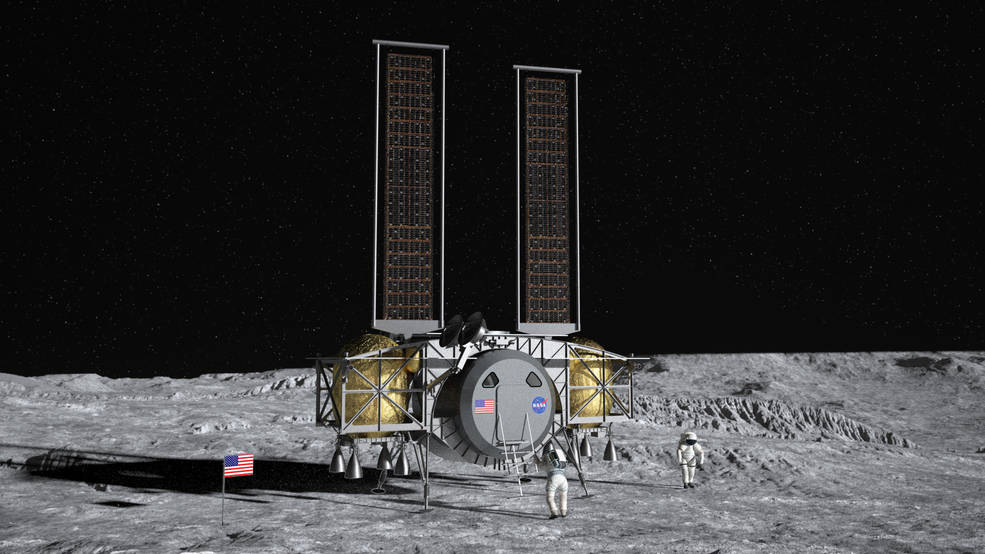

[caption id="attachment_99097" align="alignnone" width="985"]

Dynetics Human Landing System. Courtesy: Dynetics[/caption]

The Blue Origin Mk 2 lander design was originally bypassed for the initial HLS, in favour of Starship, but later returned to NASA's lunar exploration plan as a follow-on lander. The choice of Starship as the initial HLS was mainly because its development was much further than the other designs and was thus deemed to have less technical risk. Kathy Leuders, who originally made the decision as NASA's then head of human space exploration, was controversially allowed to leave NASA to join SpaceX - the firm she had chosen.

Proponents of using Blue Origin's lander is that it needs many less refuelling operations compared to the 10+ needed by the Starship HLS per landing and is likely to be more stable at landing due to its shorter stature. However, its Mk 2 lander is aimed for an Artemis V mission in 2030, and some have suggested that instead it might be faster to convert its already flying uncrewed Mk 1 version to create a small human lunar landing craft.

Other firms could compete lunar landers - possibly without using complicated cryogenic propellants that both SpaceX and Blue Origin use. Lockheed Martin is believed to be working on such a lander. Dynetics was also an original contender for the HLS contract. While a much simpler lunar lander using non-cryogenic storable propellants would have been, in many ways, a much better choice for the early Artemis missions, in reality time has run out for one of these.

In other words, Blue Origin is now the likeliest contender running against Starship for the Artemis HLS. As you can imagine, Elon Musk is not happy and has publicly derided Blue Origin's orbital space launch record: it has yet to launch to orbit.